Chapter 3 Using R Markdown

Before going into more details of R Markdown, let’s talk about two common options in the world of R coding: the R script (.R) and the dynamic R Markdown document (.Rmd).

R Scripts: Imagine coding as crafting a detailed recipe of R commands—a script—that guides R through specific tasks. Conventional R scripts (.R files) are dedicated to these commands, handling calculations and operations. However, as scripts grow, they become complex and sharing insights alongside code becomes challenging.

R Markdown: R Markdown (.Rmd) elevates the coding experience by harmonizing code with explanatory text. Within an R Markdown document, code blocks act like individual scripts—smaller, more focused units. These blocks merge code with explanations seamlessly, creating a coherent narrative. Unlike isolated scripts, R Markdown emphasizes both code functionality and its significance within the context. For these reasons, we’ll be sticking to working in .Rmd files.

In a nutshell, R Markdown allows you to analyse your data with R and write your report in the same place (this entire book was written with R Markdown). This has loads of benefits including a reproducible workflow, and streamlined thinking. No more flipping back and forth between coding and writing to figure out what’s going on.

Let’s run some simple code as an example:

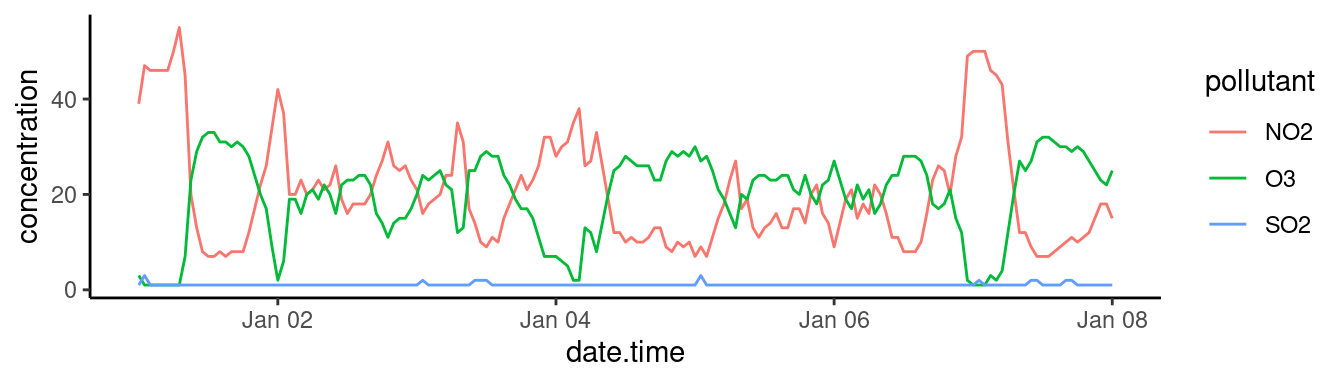

## [1] 4What we’ve done here is write a snippet of R code, ran it, and printed the results (as they would appear in the console). While the above code isn’t anything special, we can extend this concept so that our R Markdown document contains any data, figures or plots we generate throughout our analysis in R. For example here is a time series of 2018 ambient atmospheric O3, NO2, and SO2 concentrations (ppb) in downtown Toronto:

library(tidyverse)

library(knitr)

airPol <- read_csv("data/2018-01-01_60430_Toronto_ON.csv")

ggplot(data = airPol,

aes(x = date.time,

y = concentration,

colour = pollutant)) +

geom_line() +

theme_classic()

sumAirPol <- airPol %>%

drop_na() %>%

group_by(city, naps, pollutant) %>%

summarize(mean = mean(concentration),

sd = sd(concentration),

min = min(concentration),

max = max(concentration))

knitr::kable(sumAirPol, digits = 1)| city | naps | pollutant | mean | sd | min | max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 60430 | NO2 | 20.5 | 11.5 | 7 | 55 |

| Toronto | 60430 | O3 | 19.7 | 8.7 | 1 | 33 |

| Toronto | 60430 | SO2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 3 |

Pretty neat, eh? You might not think so, but let’s imagine a scenario you’ll encounter soon enough. You’re about to submit your assignment, you’ve spent hours analyzing your data and beautifying your plots. Everything is good to go until you notice at the last minute you were supposed to subtract value x and not value y in your analysis. If you did all your work in Excel (tsk tsk), you’ll need to find the correct worksheet, apply the changes, reformat your plots, and import them into word (assuming everything is going well, which it never does with looming deadlines). Now if you did all your work in R Markdown, you go to your one .rmd document, briefly apply the changes and re-compile your document.

A lot of scientists work with R Markdown for writing their reports for numerous reasons:

- Integrated Workflow: Combines narrative, data analyses, and visualizations in one document, promoting reproducibility and transparency.

- Versatility: Easily exports to diverse formats like HTML, PDF, and Word, catering to different dissemination needs.

- Plot Management: Offers precise control over visual presentations, allowing for tailored figure sizes, resolutions, and formats.

In sum, R Markdown provides a streamlined platform for scientific communication, merging data analysis with polished publication seamlessly.

3.1 Getting Started with R Markdown

As you’ve already guessed, R Markdown documents use R and are most easily written and assembled in RStudio. If you have not done so, revisit Chapter 1: Intro to R and RStudio. Once setup with R and RStudio, you’ll need to install the R Markdown and tinytex packages by running the following code in the console:

# These are large packages so it'll take a couple of minutes to install

install.packages("R Markdown")

install.packages("tinytex")

tinytex::install_tinytex() # install TinyTeXThe R Markdown package is what we’ll use to generate our documents, and the tinytex package enables compiling documents as PDFs. There’s a lot more going on behind the scenes, but you shouldn’t need to worry about it.

Now that everything is set up, you can create your first R Markdown document by opening up RStudio, selecting File -> New File -> R Markdown.... A dialog box will appear asking for some basic information for your R Markdown document. Add your title and select PDF as your default output format (you can always change these later if you want). A new file should appear using a basic template that illustrates the key components of an R Markdown document.

3.1.1 Understanding R Markdown

Your first reaction when you opened your newly created R Markdown document is probably that it doesn’t look anything at all like something you’d show your prof. You’re right, what you’re seeing is the plain text code which needs to be knit to create the final document. When you create a R Markdown document like this in R Studio a bunch of example code is already written. You can knit this document (see below) to see what it looks like, but let’s break down the primary components. At the top of the document you’ll see something that looks like this:

---

title: "Temporal Analysis of Foot Impacts While Birling Down the White Water"

author: "Jean Guy Rubberboots"

date: "24/06/2021"

output: pdf_document

---This section is known as the preamble and it’s where you specify most of the document parameters. In the example we can see that the document title is “Temporal Analysis of Foot Impacts While Birling Down the White Water”, it’s written by Jean Guy Rubberboots, on the 24th of June, and the default output is a PDF document. You can modify the preamble to suit your needs. For example, if you wanted to change the title you would write title: "Your Title Here" in the preamble.

3.1.1.1 Output Options in R Markdown

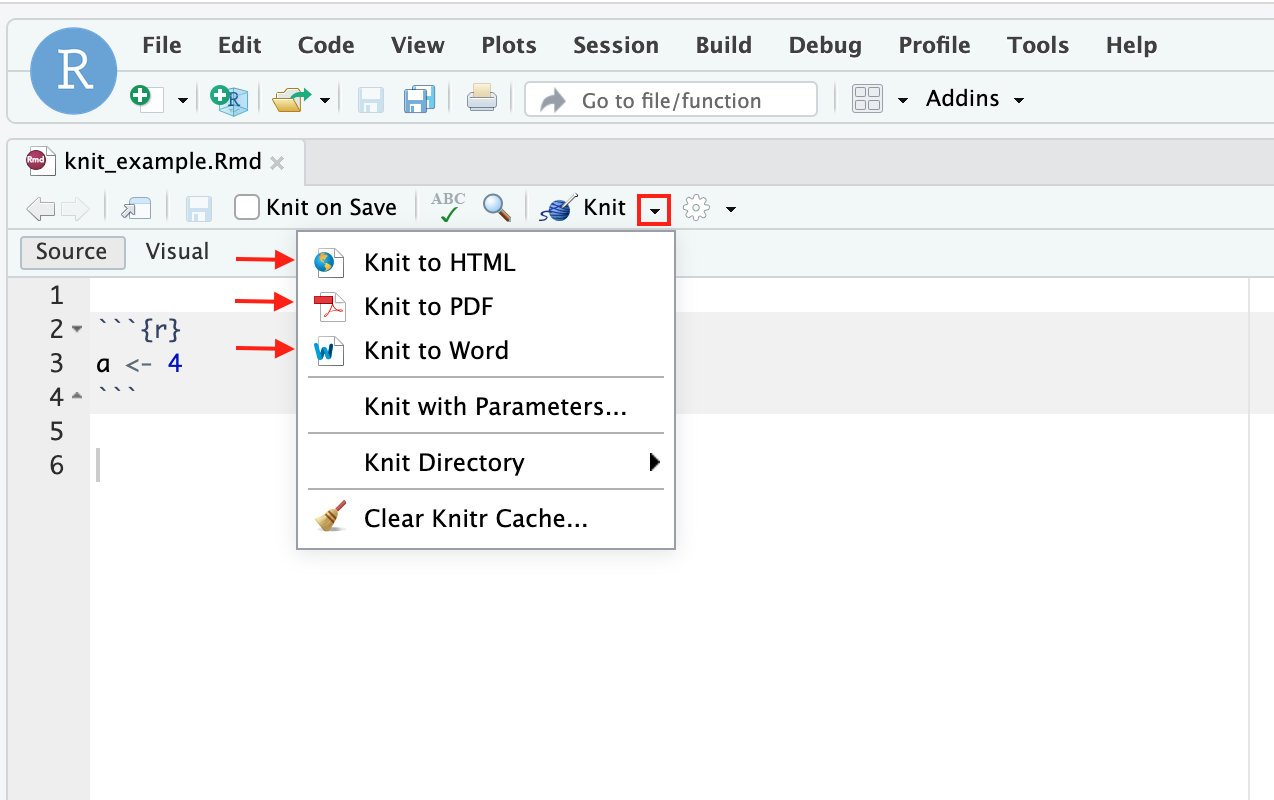

You can compile your entire document using the Knit document button. This is a great way to tinker with your code before you compile your document. Knitting will sequentially run all of your code chunks, generate all the text, knit the two together and output a PDF. You’ll basically save this for the end.

R Markdown offers flexibility in terms of output formats, allowing users to knit their documents into various outputs tailored to their needs.

Three Common Output Options:

HTML (

html_document): Produces an HTML file, suitable for hosting on websites or for sharing via email. This format allows for interactive content, making it ideal for interactive graphs or web applications.PDF (

pdf_document): Creates a PDF file. This format is best for documents intended for print or formal submissions, as it maintains consistent formatting across different devices and platforms.Word (

word_document): Generates a Microsoft Word document, which can be useful when sharing drafts or collaborating with colleagues who use Word for edits.

Controlling the Output:

Modifying the metadata header: You can change the output format directly in the header of your R Markdown file. In the last example, replacing

output: pdf_documentwithoutput: html_documentoroutput: word_documentwould knit the document into HTML or Word, respectively.Using RStudio’s Knit Button: In RStudio, at the top of the script editor pane, there’s a Knit button. Clicking the small dropdown arrow next to this button allows you to choose the output format you desire. Selecting one of the options will knit the document into that format and update the header accordingly.

3.1.2 Running Code in R Markdown

3.1.2.1 How to Create Code Chunks

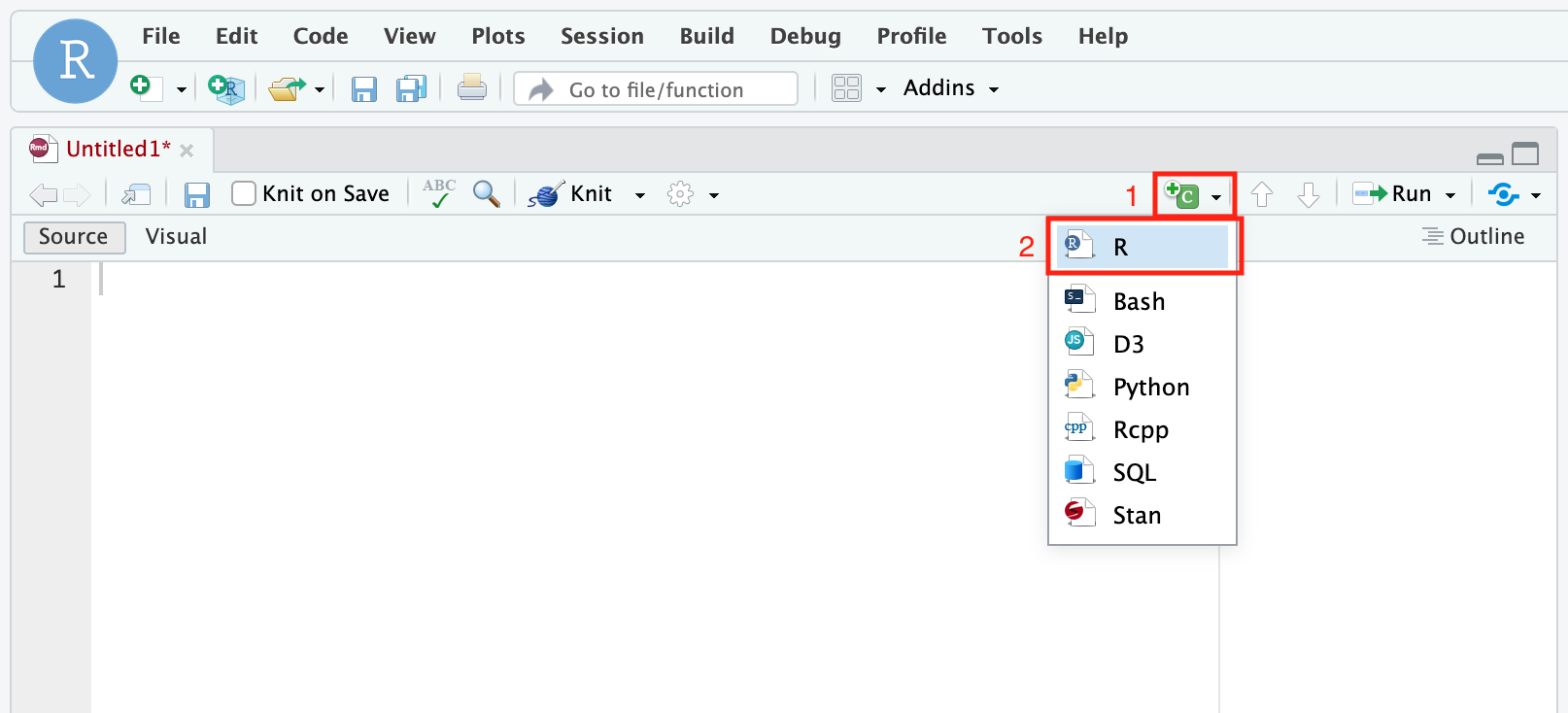

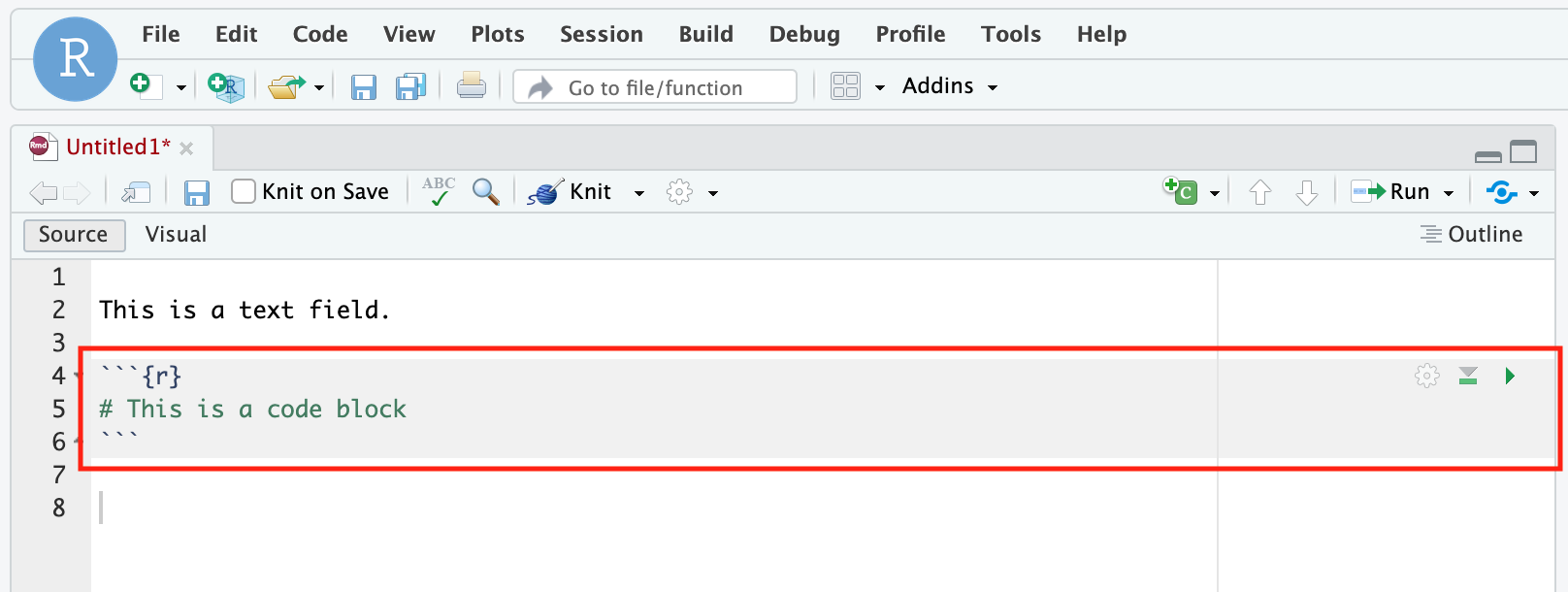

To create a code chunk within RStudio, you have several options:

Use the green “c” button located at the top right corner of your file view and select “R”. Make sure your cursor is positioned at the desired location within your .rmd file when you do this.

Type

```{r}– three back-ticks followed by{r}– to initiate a new code chunk, and type```– three backticks (```) – to end the code chunk. You can specify code chunk options in the curly brackets. i.e.```{r, fig.height = 2}sets figure height to 2 inches. See the Code Chunk Options section below for more details.

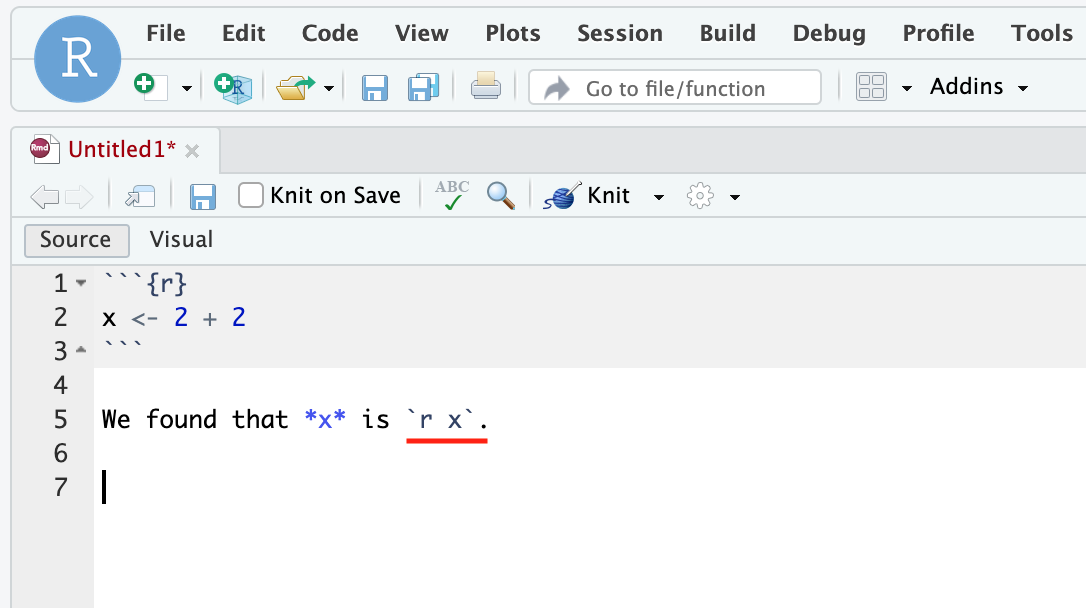

Inline code expression, which starts with

`rand ends with`in the body text. Earlier we calculatedx <- 2 + 2, we can use inline expressions to recall that value. When we knit the markdown file shown in the figure, the knitted document will say “We found that x is 4.”

When we knit the markdown file shown in the figure, the knitted document will say “We found that x is 4.”

3.1.2.2 How to Run Code Chunks

To run code within an R Markdown document, you again have various options to choose from.

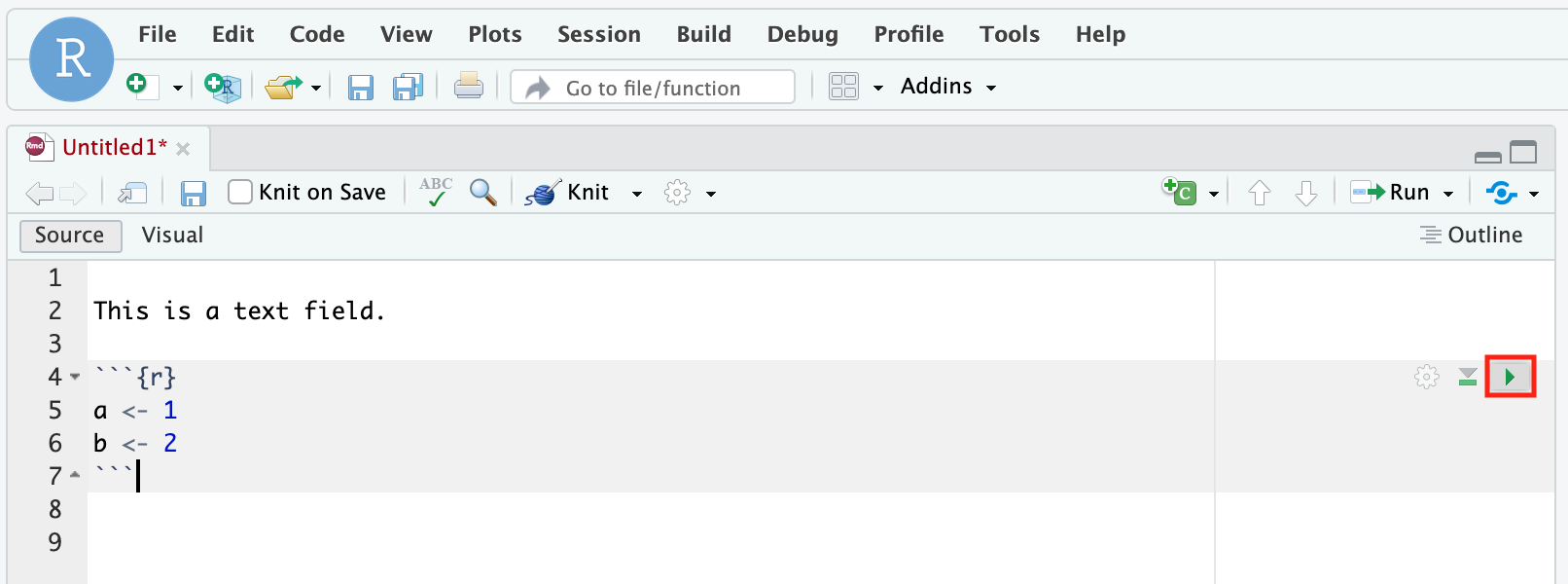

You can run a specific code chunk by clicking the green triangle button located within each chunk. This action will execute the entire chunk, including all the code it contains.

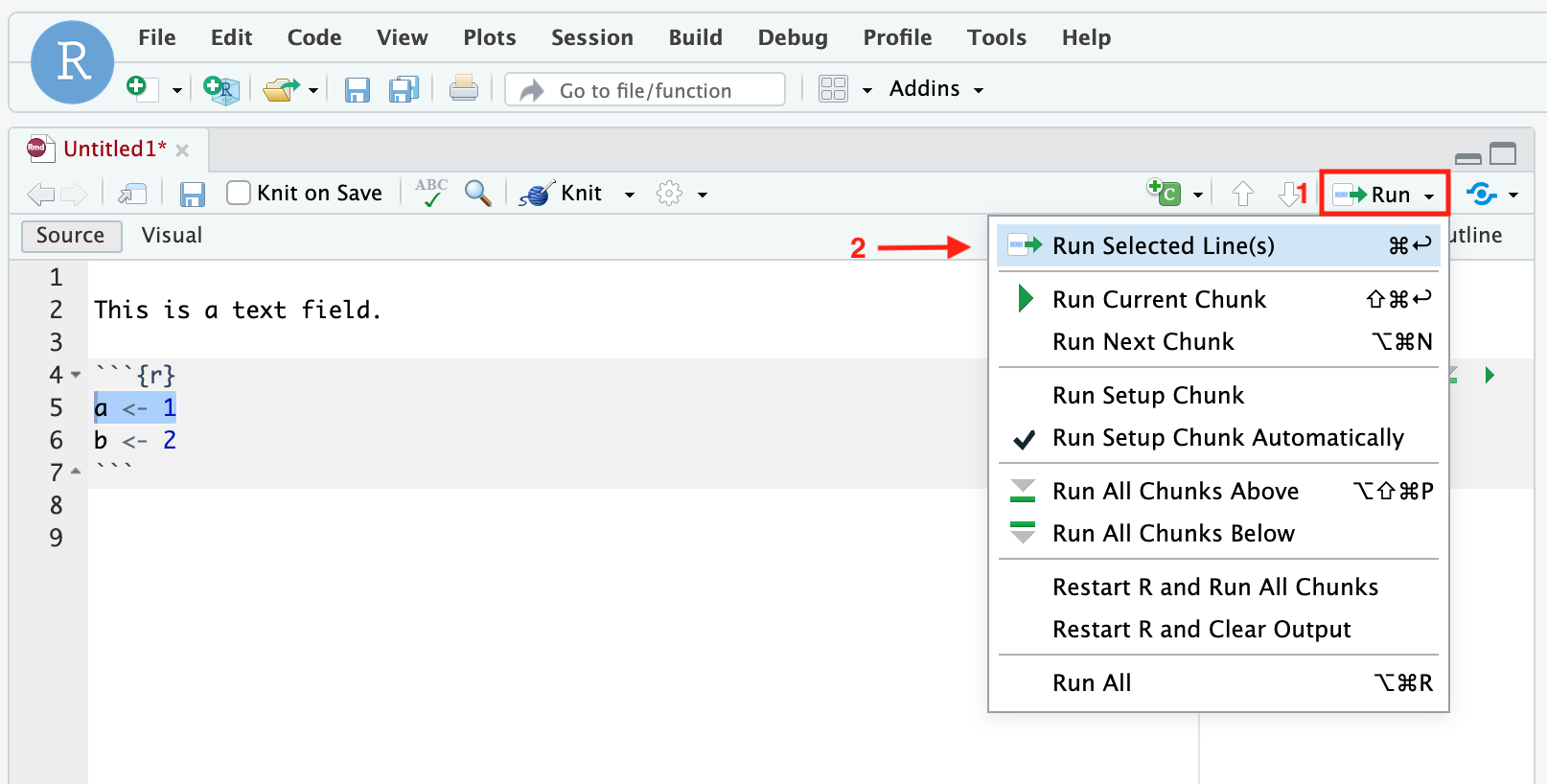

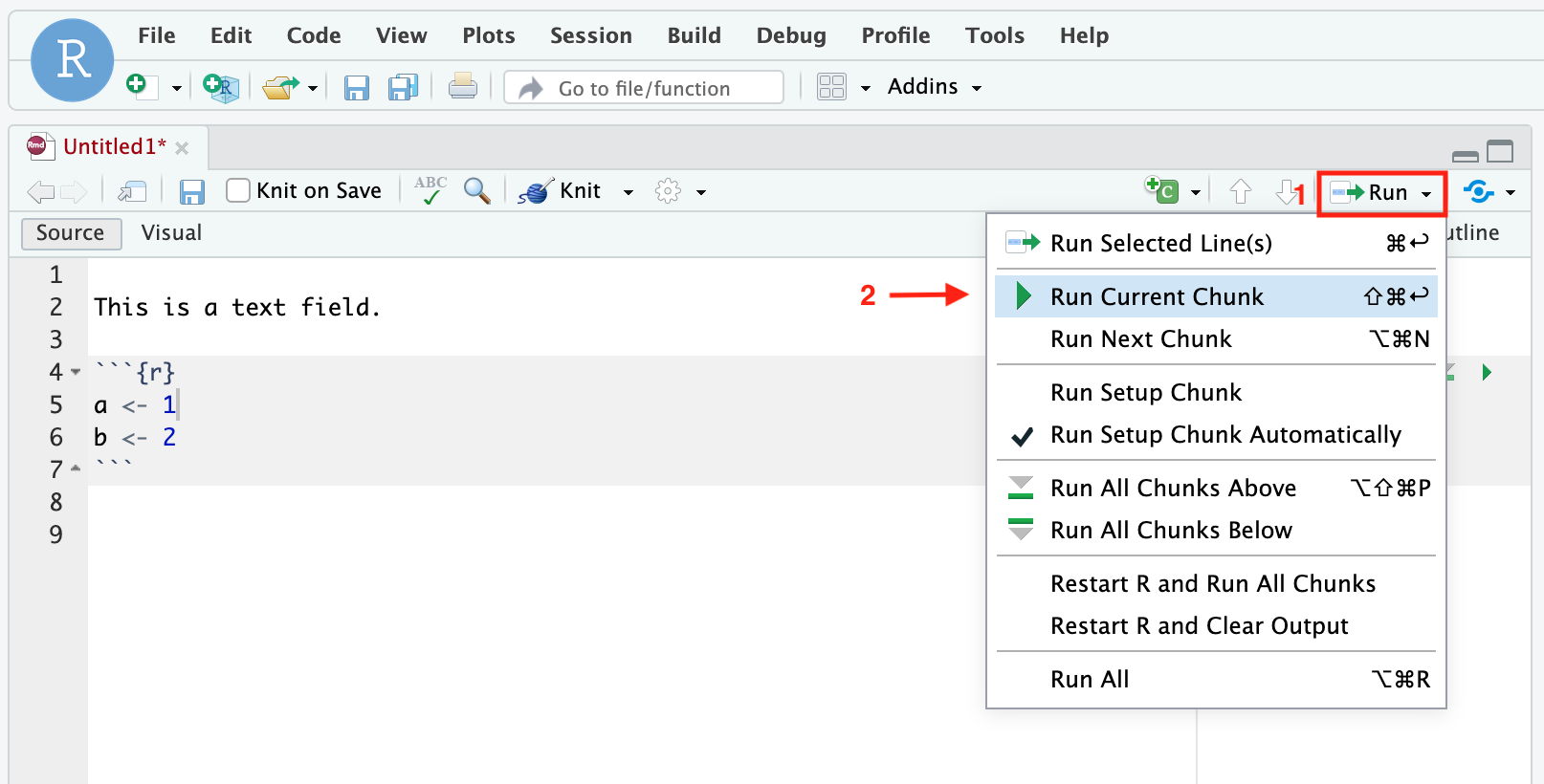

For more control, you can run selected lines or chunks. To do this, use the “Run” button at the top of the file view. This button provides a range of execution options that allow you to run code in a manner that suits your needs.

Note all the code chunks in a single document work together like a normal R script. That is, if you assign a value to a variable in the first chunk, you can use this variable in the second chunk. Also note that every time you knit an R Markdown document, it’s done in a “fresh” R session. If you’re using a variable that exist in your working environment, but isn’t explicitly created in the document, you’ll get an error.

3.1.3 Headings and Subheadings

Structure your document with clear headings and subheadings by using the pound (#) sign. This not only helps in organizing content but also aids in creating a table of contents if required.

The level of heading is denoted by the number of # signs, as you saw with R script headings in the previous section.

- Main Headings: Use a single pound sign (i.e.

# Main Heading) - Subheadings: Increase the number of pound signs based on the level of the subheading.

## Subheading Level 1### Subheading Level 2#### Subheading Level 3

R Markdown will automatically format these appropriately when the document is knit. For example, a main heading will typically appear larger and bolder than its subheadings, like this:

By effectively utilizing headings and subheadings, you can provide clear structure and flow to your document, making it more readable and navigable for your audience.

3.1.4 LaTeX Basics

LaTeX (pronounced “lay-tech”) is a typesetting system that’s popular in academia due to its high-quality output format and the ability to handle complex formatting tasks. It’s especially favored for documents that contain mathematical symbols, equations, and other specialized notation.

In R Markdown, LaTeX code can be integrated directly into text chunks to allow for advanced formatting, especially for mathematical expressions and equations. When you knit your R Markdown document, the LaTeX code is rendered into beautifully formatted text. Note: LaTeX code should always be written in text chunks, not code chunks!

There are two common ways to turn your expressions in a math mode.

- Display mathematical expressions: centers the mathematical expression on its own line.

- Inline mathematical expressions: appears within the text of a paragraph.

For chemistry students, one common use of LaTeX is to typeset chemical equations. We will provide examples on the combustion of methane:

3.1.4.1 Display math mode

You can have an entire line in a math mode using either \[...\] or $$...$$.

For example, writing the following in R Markdown

\[ \text{CH}_4 + 2\text{O}_2 \rightarrow \text{CO}_2 + 2\text{H}_2\text{O} \]

produces the following output in the generated PDF:

\[ \text{CH}_4 + 2\text{O}_2 \rightarrow \text{CO}_2 + 2\text{H}_2\text{O} \]

3.1.4.2 Inline math mode

On the other hand, if you want to insert your expression within your sentence, you can use $...$ syntax.

With our methane combustion example, we can write something like this:

Methane ($\text{CH}_4$) reacts with oxygen ($\text{O}_2$) to produce carbon dioxide ($\text{CO}_2$) and water ($\text{H}_2\text{O}$).

When you knit it, this will be displayed as:

- Methane (\(\text{CH}_4\)) reacts with oxygen (\(\text{O}_2\)) to produce carbon dioxide (\(\text{CO}_2\)) and water (\(\text{H}_2\text{O}\)).

3.1.4.3 Useful LaTeX Syntax

Now that you’ve seen how you can write your scientific expression in two different ways, let’s look at some useful LaTeX Syntax for our purpose.

- Symbols

- Greek letters: Use a backslash followed by the name of the letter, e.g.,

\alphafor \(\alpha\). - Special symbols

\timesfor \(\times\)\approxfor \(\approx\)\geqfor \(\geq\)\rightarrowfor \(\rightarrow\)

- Greek letters: Use a backslash followed by the name of the letter, e.g.,

- Superscripts and Subscripts

- Superscripts:

x^2renders as \(x^2\). - Subscripts:

H_2Orenders as \(H_2O\)

- Superscripts:

- Formatting

- Boldface:

\textbf{Text}for \(\textbf{Text}\) - Italics:

\textit{Text}for \(\textit{Text}\)

- Boldface:

Tip: In RStudio, you can place your cursor over LaTeX code to preview its generated output.

3.1.4.4 More LaTeX Resources

There are numerous online resources dedicated to LaTeX symbols and their usage.

- A popular starting point is the Comprehensive LaTeX Symbol List. This extensive compilation offers a wide range of symbols used in various disciplines.

- Platforms like Detexify allow users to sketch a symbol, and the tool then identifies the corresponding LaTeX command.

- Engaging with online communities, such as the TeX Stack Exchange, can also be invaluable for finding specific symbols or seeking advice on LaTeX-related challenges.

3.2 Compiling your final report

To hand in your work, you’ll need to knit your document to generate a PDF. To knit your R Markdown file, click the knit button in RStudio (yellow box, Figure 2).

3.4 R Markdown resources

There’s a plethora of helpful online resources to help hone your R Markdown skills. We’ll list a couple below (the titles are links to the corresponding document):

- Chapter 2 of the R Markdown: The Definitive Guide by Xie, Allaire & Grolemund (2020). This is the simplest, most comprehensive, guide to learning R Markdown and it’s available freely online.

- The R Markdown cheat sheet, a great resource with the most common R Markdown operations; keep on hand for quick referencing.

- Bookdown: Authoring Books and Technical Documents with R Markdown (2020) by Yihui Xie. Explains the

bookdownpackage which greatly expands the capabilities of R Markdown. For example, the table of contents of this document is created withbookdown.